Feeling Festive

In most parts of the world red is the color of celebration, it has been associated with power, divine protection and wealth. This may be, in part, because Primary Red is not an easy color to extract from natural dyes. The process is complicated, frequently dangerous and costly. In Medieval Europe the recipe make the bright red cloth for soldier’s uniforms, or cardinal’s cloaks, was a closely guarded secret. Before the Spanish brought cochineal from the New World, the most common red was made with madder roots.

Until the invention of chemical dyes, ordinary people could not afford colorfully dyed fabrics. The dye stuff readily available made tans, yellows and some shades of green. Indigo would be the biggest exception, with its many shades of blue. Generally speaking, even members of royal families had limited access to dyed fabric.1

Those with the means, could add some color to their garments with bits of stitchery, or accessories such as amulets or jewelry. The color red, rare and linked to power, came to be associated with protection and strength. Many ancient white linen garments are marked with a bit of red wool embroidery. 2

Cochineal

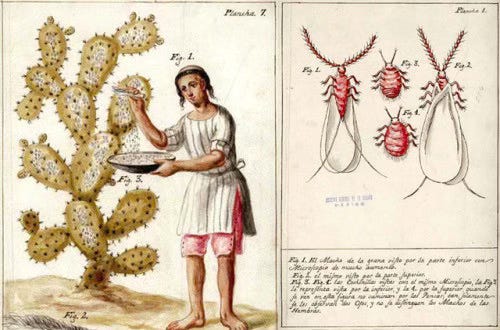

Cochineal is a dye that the Spanish “ discovered”when they came to Aztec and Mayan Cities. It has a fascination history. Until the Conquistadors brought some back to the Old World with them, reds came from only a few plants. everyone, even the Pope, was delighted with access to a bright, clear red dye.3

Spring Fair at Oil and Cotton

I was asked to do a dye pot demo at Oil and Cotton for our Spring Fair, so I thought it would be fun to make a vat of Cochineal Dye. It was a lot of work, but also lots of fun. I used insect carcasses from Botanical Colors. Only a small amount of bugs are needed.

While I try to be as precise as I can about the history of textiles, I take a much more relaxed view with natural dyes. Firstly, there is the chemistry, to control the results of a dye-vat every thing has to be taken into consideration: time, temperature, the ph of the water, the quality of the dye-stuff as well as the mordants, the pots used, the condition of the fabric(s).

On that last point, cellulose fibers (cotton, linen, ramie, nettle, etc) take dye completely differently than protein fibers (silk, wool, alpaca, etc). Yarn reacts differently that fabric. If your materials have been dyed in the wool then the color is probably visible all the way through the yarn. Materials dyed in the yarn or fabric stage, tend to have flecks of undyed fibers.

With a Community Dye Pot, the variables increase exponentially as each person prepares and then enters their piece into the dye pot. Like stone soup, but with more complicated chemical reactions. Then we made it even more complicated by adding hibiscus flowers (they yield a nice pink and smell way better than cochineal) and dried blue-pea flowers for some bundle dyeing.

The day was a big success, with more shades of pinks and mauves than we could have planned for. Plant based dyes (and paint pigments) can be a source of unending exploration.

I hope to do some more dye pot events in the near future!

This does not mean everyone one was dressed in brown. In a recent episode of Haptic and Hue, Our Host Jo Andrews, tells us about The Forgotten Medieval Craft of Cloth Staining.

Linen is famously difficult to dye. The attributes that make linen such a wonderful cloth also make it resistant to stains and dyes. The Egyptians discovered how practical linen fabric can be. Linen garments were sometimes embellished with red, patterned embroidery as a sort of talisman for the wearer. Here is a link to a magnificent study of this practice.